A collaboration between the CSIR speech node, a private speech technology company, SAIGEN, and SADiLaR has resulted in an automatic speech caption technology, to be used by Government Communications Information Systems, to ensure greater accessibility of government communications to South Africans.

Video has become ubiquitous in society, be it news, marketing, entertainment and even educational material, we currently live in a video first world. But video, as an audio-visual medium, is not accessible to everyone. For the hard-of hearing or deaf community and second language English speakers it can be extremely challenging to engage with important messages delivered by video. Speech captions are the obvious and elegant solution to this problem. This is the prefered option for communication from the hard-of-hearing community and there is also much evidence showing that second-language speakers retain much more information from a video if it is accompanied by sub-titles or speech captions.

“But speech captions do not simply fall out of a hat,” says Jaco Badenhorst a researcher of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). “It is a very labour-intensive and time consuming task for a video editor.”

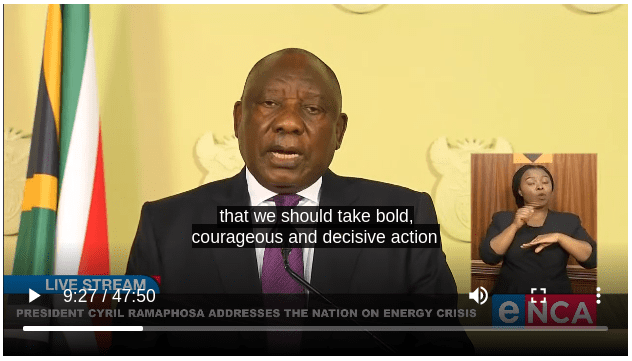

During the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying lockdowns government communications, particularly President Cyril Ramaphosa’s ‘family meeting’ addresses to the South African nation were critical. It was a time of crisis and it was imperative that all South African households were able to watch and engage with what the President was saying. It was therefore no coincidence that it was during this period that the Government Communication and Information System (GCIS), the government department responsible for communication, reached out to the CSIR for an automated speech recognition system that could, with near perfect accuracy, generate automatic speech captions for government speeches.

“To be as effective as possible, this needed to be a South African made system built on South African accents and dialects,” explains Badenhorst. “While there are a number of commercial options abroad which do this, their software will not accurately pick up the many variations of South African accents and this will mean much more work down the line to edit and correct the automated transcript.”

The SADILaR connection

The CSIR is home to the SADiLaR Speech Node with an existing focus on speech technologies including automatic speech recognition and text-to-speech technology. Although they had existing capabilities for this kind of technology development, the project was daunting.

Knowing this would be an expensive, but a very worthwhile endeavour, the team at the CSIR wrote a proposal for funding to SADiLaR.

“SADiLaR is an enabling infrastructure,” says Juan Steyn, project manager at SADiLaR. “So our mandate is to support the development and distribution of technology which will build our South African language resources and contribute to the good of our multilingual society.”

Funding a system to generate automatic speech captions for government communications was therefore a natural fit for SADiLaR. Especially because it meant this technology would then be available locally for other uses.

The SAIGEN connection

Fortunately for all players involved, a chance encounter between the team at the CSIR and a private company, SAIGEN, in the very early days of the project, revealed that SAIGEN was working on a very similar product which could form the base of the GCIS tool.

SAIGEN was formed back in 2017 by two former academics, Dr Charl van Heerden and Professor Etienne Barnard, who specialised the building of automatic speech recognition technology for under-resourced languages. Van Heerden used to be part of the CSIR and worked with Badenhorst, and it was through this connection that two groups became aware of the overlap.

“SAIGEN offers a number of commercial speech recognition products, including a call centre speech analytics product and a speech recognition product for media monitoring companies,” says van Heerden. “When we first became aware of the GCIS request to CSIR we had already developed an automatic speech recognition prototype, which we planned to license for those who needed automated transcription services.”

As it became clear that many of the base components that would be needed for the GCIS tool formed part of the SAIGEN prototype the CSIR reached out to SADILAR to adjust the funding proposal and strategy.

“Recognising that this was funded with public money, and that reinventing the wheel would be wasteful expenditure, all parties happily agreed to this collaboration,” says van Heerden.

Project requirements

The first element of the project was the generating of automated speech captions for the speeches of the President, Deputy President and cabinet ministers. This product is to allow the GCIS to be able to release the videos of government speeches with accurate captions in minimal time.

“The mandate was to make a system that would generate captions to be as near accurate as possible,” says Badenhorst. “Recognising of course that no system can do this perfectly. The product includes an interface in which the captions appear alongside speech, with those words the system is less confident about highlighted. The GCIS staff can then quickly and easily correct the captions where necessary.”

The goal also is that the system be customised to individual speakers through a speaker recognition system. This means the software would be trained on the speech of individual speakers for even greater accuracy of captions.

Another deliverable, this one for SADiLaR, is to deliver a text and speech corpus (a language resource) that could be added to the SADiLaR repository and used in the development of other language technologies or for research purposes. The GCIS has an archive of videos and speeches it was agreed with them to access this data and compile such a corpus to be made available in the public domain.

The corpus will be delivered to SADiLaR by the end of September 2022.

The final product and the way forward

The project is now in its third and final year of completion. One pilot was held with the GCIS, in which four GCIS staff members, including a manager, media specialist, video editor and intern, tested the tool. The feedback, fortunately, was very positive, with all reporting that they could quickly and easily verify and correct the captions.

A second pilot is planned for later in the year in which the GCIS will test additional features they have requested, such as altering the appearance of the captions according to the medium on which the video is published.

“The second pilot will have the opportunity to finalise the offering to ensure it is fit for client needs,” says Badenhorst.

Once the tool is being used by the GCIS, the hope is that there will be commercial demand for the software.

“Beyond the accessibility needs, video captions are widely used. Our busy lives means often people will watch a video in a noisy environment, such as public transport or in a queue, or somewhere like an office where it is simply not appropriate to have sound on. In these environments captions are critical,” says van Heerden.

“And in our multilingual society where a minority are first language English speakers, captions go a long way towards ensuring comprehension and retention of the subject or speech delivered.”