24 April 2024

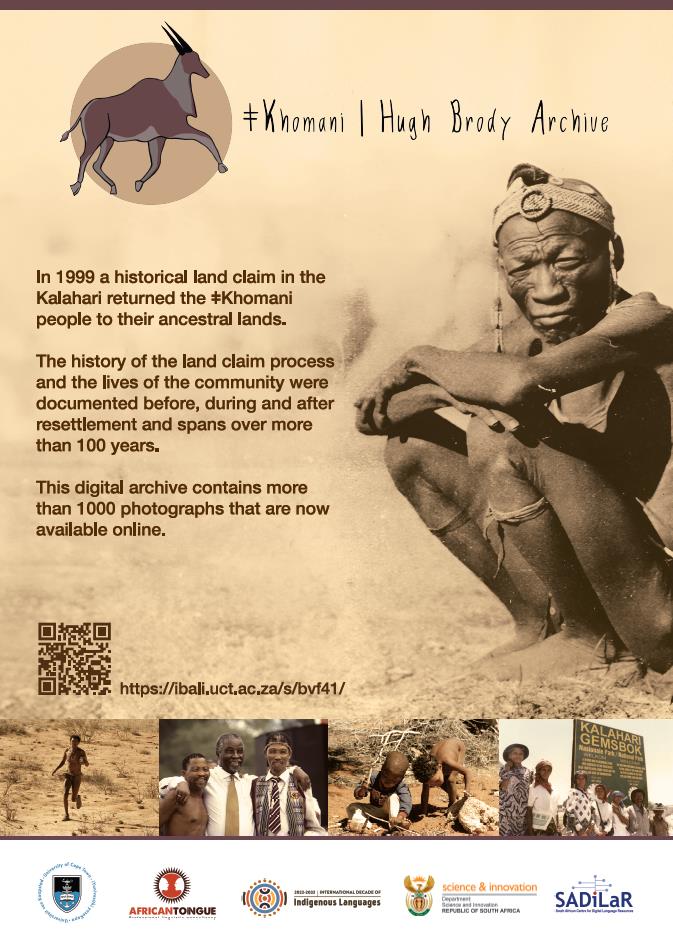

A research project, funded by the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLaR), has helped realise the long-held dream of South Africa’s ǂKhomani community to share their proud history with the rest of the world.

Dr Kerry Jones, director of African Tongue and research lead on the project, has worked tirelessly with her research partners in the southern Kalahari to identify, digitise and develop metadata for a large body of historical photos that are held at the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Special Collections Library, as part of the ǂKhomani | Hugh Brody Collection.

“It is the first project on the African continent to be registered with UNESCO’s International Decade of Indigenous Languages,” Dr Jones remarks. “These resources are not just a national treasure but a global one.”

The ǂKhomani are among the first known people to live in the southern region of the Kalahari, in the far northwest corner of South Africa. They have lived as hunters and gatherers in this vast desert landscape for generations and yet their proud heritage and rich language was nearly lost to their descendants and the world.

“This special collection holds all the materials that were generated over 15 years of work with the ǂKhomani by various researchers,” says Jones. “It also includes over 130 hours of original film footage, detailed local maps, family trees, audio clips and transcripts of oral history collected in four different languages (Nǀuu, Nama, Kora and Afrikaans) – all of which is still to be digitised in the near future, pending availability of funding.”

According to Jones, digitising the more than 1000 photos (which span over 120 years, from the Kalahari to Kagga Kamma and back again) involved language verification, orthography standardisation, and the development of metadata for all photographs in the collection.

“This includes the standardisation throughout the collection of traditional names transcribed in N|uu, Kora, or Khoekhoegowab. For example, in instances where a photograph has a description of places or names of people, these will be transcribed in the original source language using modern orthography practices, using standardised Unicode throughout the collection to make the content uniform and digitally findable,” she explains.

Extensive community consultation

Jones worked closely with the ǂKhomani community to help identify the people and places in the photos.

“The primary researchers were myself and Francoise Betta Steyn, who has been working with African Tongue for more than eight years now and specialises in the Afrikaans variety ‘Onse Afrikaans’, which is spoken mostly in the Northern Cape. Then we had extensive consultation in identifying all the people in the images, with community members such as Petrus Vaalbooi (the traditional leader of the ǂKhomani people), Lydia Kruiper, Izak Kruiper, Oulet Kruiper, OupaJan Pietersen, Katriena Bock, Sussie Bock, Gesina Brou, Lys Tieties, Anna Bojane, Claudia Snyman, Collin Low, Elizabeth Tieties, Dr Katrina Esau (the last-known fluent speaker of N|uu), Lisbet Bok, Sensie Mondzinger and Meester Willem Damarah.”

The project also entailed developing a digital project showcase on Ibali, UCT’s digital collections platform, using Omeka-S software. “We worked directly on Ibali to develop the content with training provided by UCT’s Digital Libraries Services – Dr Sanjin Muftic was outstanding in helping us standardise this process! The digital photo archive allows a user to search for images according to three main categories – person, place, or keyword – and each photograph includes detailed additional information, such as when and where the photo was taken, who the photographer was, on which type of camera, and so on,” Jones comments.

“Furthermore, we developed instructional material for the local community and general public on how to access this photo archive in both English and Afrikaans, Afrikaans being the lingua franca of the Kalahari. We also presented training sessions and workshops on how to work with this new resource to local community members, librarians, and educators in both Upington and the Kalahari.”

Working in extreme conditions

Working on location in the Northern Cape brought many challenges for Jones and her team.

“Extensive loadshedding when working on location in the Northern Cape made things very difficult. Luckily, I had made printed handouts and duplicates so that we could work old school, with paper and pen. If I didn’t have those backups, we would have been totally stubbed. An entire transformer in Askham went out, affecting us and many other towns. We had no power and no comms on location in extreme heat in the Kalahari of over 40 degrees! Power outages in Upington are also unpredictable and the power can be off for days at a time. This is far beyond local loadshedding – there’s a power crisis in the Northern Cape.”

In addition to this, the area has severely limited internet access. “Though new community centres and libraries with internet access have recently been built in the Kalahari (which we used as venues to provide online training to the community), the power issues continue and some of the libraries currently don’t have internet access, despite having a new system,” Jones notes. “And in Andriesvale, the library has no computers or internet at all, which meant that community members had to do all their training on mobile devices.”

Showcasing the ǂKhomani people’s unique heritage

Completing the first portion of the digital ǂKhomani | Hugh Brody Archive comes as a huge relief to Jones and her hardworking team.

“We hope that this example will show what we are capable of and showcase South Africa’s unique heritage and linguistic diversity (which will be more evident when the transcript files go live on Ibali in September 2024). We still have a long way to go with the rest of the collection but we’re working on it. I think it’s very important to prioritise community engagement and accessible public feedback. It’s been so many years since the inception of this work and the ǂKhomani people and the general public can finally access these resources on a user-friendly platform.”

Following the community workshops and training in the community, the feedback was overwhelmingly positive. “Petrus Vaalbooi acknowledged how important it is for their heritage and history to be represented in the digital space for future generations and for their stories to be told. The ǂKhomani narratives are very important threads in the stories of our shared history. Youngsters were happy and excited to see their grandparents and parents online. In some cases, there were pictures of today’s youth as babies – it was fun to find pictures of family online and for community members to share with each other,” she recalls.

A proud partnership with SADiLaR

“Our team is very grateful for the support from SADiLaR to do this very meaningful work,” Jones adds. “This is African Tongue’s second collaboration with SADiLaR. The first was with Prof Menno van Zaanen in developing the N|uu Namagowab Afrikaans English dictionary and associated web portal and app Saasi Epsi. Our dictionary has since become an award-winning publication that we are very proud of.

“We hope that this digital archive will be just as impactful and noteworthy and that the working relationship between African Tongue and SADiLaR will continue to grow from strength to strength. It is our priority to produce quality language and heritage outputs to assist with documentation, preservation, and maintenance of our nation’s endangered languages.”

* Visit the ǂKhomani | Hugh Brody Archive here. The photo component of the collection went live in March 2024, and the next component, ‘Films and Transcripts’ is expected to be launched in September 2024.

(Written by Birgit Ottermann)